The San Andreas Fault: I-15 to I-5

The Amazing San Andreas Fault, I-15 to I-5

What? You've never been to California's most infamous geological feature? You've never explored the only fault most people know by name? Really!?!Why You Can’t Miss It

It’s the San Andreas! The real thing! It’s one of those things visiting aliens would see from their space ships and be glad they don’t have one at home. It’s the stuff of legend and myth. It’s a scar on the continent. It’s not just a place where big earthquakes can happen and the central character in so many bad movies, this particular section is the reason southern California has so many earthquakes – it’s the “big bend” of the San Andreas, home to awesomely unique and thought-provoking landscapes and geologic features. It also happens to be one of the best country drives in southern California.

Do something different with family visiting from out of state -- get outta the theme parks and head for the hills!

Do something different with family visiting from out of state -- get outta the theme parks and head for the hills!

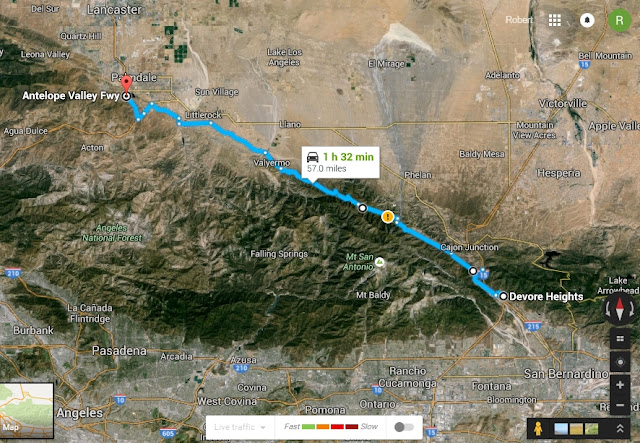

Time: ½ day to 1 day. Devore (I-15/I-215 interchange) to Frazier Park (I-15 at the Grapevine) is about 114 miles, plus mileage back into So Cal, about 3 hours driving time.

Difficulty: easy; no hiking necessary

Vehicle: Any. Off-roading is available.

Geology of the San Andreas Fault

North of the Los Angeles metro area, the San Andreas is bent from its north-northwesterly trend elsewhere into a nearly east-west trend called “the big bend.” This bend is the reason southern California has more faults and different earthquake hazards than northern California. It works like this: the more westerly trend of the fault creates a westward bump in North America, which sticks out like a chin that the Pacific Plate can't resist punching. At this bend, the Pacific plate is being forced under the North American plate, causing mountains to be uplifted along east-west trending thrust faults. Faults are present at all of the mountain- and hill-fronts in the Southland, and each is capable of a damaging earthquake like the M6.5 San Fernando, 1971; M5.9 Whittier in 1987 (both of which I was in); and the M6.7 Northridge quake in 1994.

|

| Map of faults of the Big Bend (USGS) |

This collision zone means that the valleys at Hollywood, San Fernando, Pasadena, and Cucamonga are subducting under the mountains. Think of it – in the distant future, all those Beverly Hills mansions will be sucked under the hills, while Dodger stadium watches it happen from on top.

Geology You'll See

· Spectacular tilted sandstone layers

· The folded edge of the continent

· Tell-tale straight valleys and ridges

· The gravel remains of ancient mountains

· Landslides

· Intersection with the Garlock fault

The San Andreas Route

You can do this route forwards or backwards, and it meshes well with the tour of the Carizzo Plain National Monument for a 2-day trip. I’ll describe it here from south to north, starting at the I-215 / I-15 interchange near San Bernardino (at Devore). Route in Google Maps

Devore to Wrightwood

Take I-15 or I-215 north toward Victorville. Where the two freeways meet is Devore, a village nestled right up to the San Andreas. It’s a pleasant place to wander through. Look for the straight ridges at the mountain front – those mark the branches of the San Andreas.

|

| Route from Kenwood Ave. to Swarthoud Canyon Road |

There’s a reason I guide you to this particular spot, and not where the interstate crosses the fault. My graduate advisor was once asked to do a live interview with Diane Sawyer on Nightline, because he had done a lot of research on it and was chairman of the Southern California Earthquake Center. The network requested that the interview be done “live from the San Andreas.” The spot he chose was up there on I-15 by this hill. When the TV floodlights came on for the broadcast, we suddenly realized what a bad idea this was – the spectacle caused a huge traffic jam! A couple thousand overworked, underpaid commuters’ fragile nerves were put on edge so an overworked, underpaid geophysicist could pick up a rock from the fault zone and crumble it in his hands on national TV. It turned out to be a good interview, but I think we should have done it away from the busy interstate.

You’re now standing at the end of a long, straight fault valley that goes northwest up to Wrightwood. This valley was eroded along the San Andreas.

Ponder this: The bedrock in the mountains to your east are part of the North American tectonic plate, and have always been attached to the continent approximately where they are now, but before there were any mountains here. On the other side of the fault, in contrast, the bedrock was sliced off the edge of the continent hundreds of miles farther south and was shifted along the San Andreas to where it is now. The two sides' proximity is coincidence -- the rocks are unrelated, and some day will again be far apart.

Go just a short way farther up Cajon Blvd. and turn left onto Swarthout Canyon Road. It swings back to the west where you came from. Cross the railroad tracks and go past the big powerline to a gravel parking lot [stop 2 34.272167, -117.465944] Walk any trail that heads away from the road to see Lost Lake. This is a “sag pond,” a depression along the fault. It’s one of the signs of strike-slip faulting. Crushed rock along the fault is more easily eroded than the surrounding bedrock, and so most of the fault is in low spots in the topography. Where conditions are right, the fault is marked by elongated ponds like this one. You can also see fault scarps on the far side of the pond and up the valley.

Take either of the powerline roads uphill toward the sandstone hills. The roads are graded gravel most of the way, but are a bit rough in places, so I recommend a vehicle with a bit of ground clearance (SUV, truck, Outback). Please consider weather and road conditions carefully!). These roads go over the hill to Lone Pine Canyon Road via a railroad side road. Once you get to to where Lone Pine Canyon Road meets highway 138, turn left onto Lone Pine Canyon Road and park in the gravel lot by the sandstone cliffs.

To stay on pavement, continue up the canyon and turn RIGHT on Lone Pine Canyon Road. After about a mile and a quarter, stop at the big sandstone cliffs. [stop 3 34.313431, -117.497003]

These spectacular cliffs are the Cajon Valley sandstone. When it was deposited by a river between 14 and 18 million years ago, it crossed the San Andreas and continued out to a delta farther west. Today, that delta is 310 km (192 miles) away near San Luis Obispo! In places, the sandstone contains pieces of granite eroded from the Mojave desert to the northeast. Look for them in the coarsest sand layers.

You might recognize these cliffs from numerous commercials, TV shows, and movies. Michael Jackson filmed part of his “Black or White” music video at one of these sandstone outcrops, and I remember an episode or two of Star Trek featuring cliffs like these as part of an alien planet.

Continue up Lone Pine Canyon Road to Wrightwood. Look at the very straight valley. It was formed by the fault – the ground-up rocks along the fault erode more easily than the bedrock on either side. Had the valley been formed by normal stream erosion, it would have had the normal curves and branches found along any stream valley. Notice that there are very few side canyons? On the way, you’ll also pass by an obvious landslide on the right side of the road. It was likely triggered by an earthquake.

Take a moment to get out and look around at the summit. You can see all the way back down to I-15 and Devore, and ahead through Wrightwood.

Wrightwood to Palmdale

Around Wrightwood, notice the bridges and drainages built to contain rocky floods and debris flows (rock flows). These mountains have been uplifted so rapidly along the San Andreas, erosion has not had time to fully reduce the slopes to stable geometries. Steep slopes and debris flows are hallmarks of very young topography.Wrightwood has another unique feature caused by the San Andreas. I heard the story of its discovery from the seismologist who saw it first. While doing some work in the Wrightwood area, he took a lunch break and lay on the forest floor. Looking up, he noticed that a couple of the tall, old pines had split, double tops. Curious, he looked around the area and found hundreds of split-top pines, all in the biggest, oldest trees. Investigating more, he learned that when a pine trunk breaks off, the tree grows a double top. A dendrologist cored the trees to get the ages of the splits. The year of all the splits? 1857, the year of the last big one on the fault. The shaking was so violent, many of the tops of the trees broke off.

At the Mountain High ski area, pull into the parking lot to look around. The main branch of the San Andreas is at the eastern edge of the parking lot, and passes right through the narrow summit of the highway.

Continue northward on road N4, the Big Pines Highway (don’t take the Angeles Crest Highway). The road pretty much follows the San Andreas all the way to Valyermo. You’ll pass a couple of sag ponds along the way. If you’re so inclined, there are several good places where you can see how different the bedrock is on either side of the fault. Relative to the east side, the west side has slid a couple hundred miles to where it is now, so the rocks formed in very different places and at different depths in the crust.

When you get to Pallett Creek [34.460697, -117.865180], you have the option to turn left on road N6 and visit the Devil’s Punchbowl [34.413966, -117.858813], sandstone layers that have been folded by pressure at the tectonic plate boundary. It’s just a couple of miles up the road, and has some pleasant, unique hikes.

Pallett Creek was the site of an important study of movement on the San Andreas that gave us good dates of past earthquakes. The site was chosen because the creek provides a frequent supply of sediment and organic matter across the fault, which closely bracket past ruptures.

Take the Fort Tejon Road toward Palmdale, and turn left on Mt. Emma Road to get back near the fault. Turn right on Cheesboro Road, then left on Barrel Springs Road, which is on top of the fault. Notice the straight scarps and color change in the soils and bedrock in person and in the aerial image below.

Notice that the aquaduct crosses the San Andreas in several places. When the fault ruptures, southern California will have water shortages for a few days -- it shouldn't take long to fix.

Turn left on Pear Blossom Highway and go all the way to Highway 14. Go north, and watch the road cuts – they display spectacularly folded rocks in a few places [34.534648, -118.116853]. Continue to Palmdale, take the exit for E Ave S, and turn right to Lake Palmdale. Its northeastern shore (the one with the big wind turbine) is the San Andreas, and it splits the two Park ‘N Ride lots. On E Ave S, the fault goes right behind the orange-tiled house near the highway.

Palmdale to Frazier Park

Take West Palmdale Blvd and Elizabeth Lake Road west out of Palmdale. The road makes its way into the linear valley of the San Andreas, where you can see numerous straight hills and scarps. Elizabeth Lake [34.669556, -118.414451] and Lake Hughs straddle the fault, filling in yet more topographic lows. At some point, road N2 becomes Pine Canyon Road. At Three Points [34.735823, -118.598763] , turn left at the green store to stay on Pine Canyon Road. Watch for linear scarps and aligned vegetation marking the fault.

I heard a great story about this part of the fault. In the 1980’s I was in a Geological Society of America meetin and listening to some ancient geologists talking – one was near 90 years old. He said when he was young, he met a cowboy out here in the high desert, who was himself about 90 at the time. The cowboy said he was riding his horse along this valley when the 1857 earthquake occurred. His horse bucked him off and then couldn’t even stand up during the shaking. He watched as the fault ruptured the ground right in front of his eyes, and the hills on the far side shifted to the right more than 20 feet. I don't know if this story is true, and it has never appeared in print anywhere that I can find, but it came from a reliable source and is entirely possible.

This section of the fault has a lot of aligned vegetation along the fault. Faults often put impermeable bedrock against permeable aquifers, so the water rises to the surface, attracting bushes and trees. Turn left on 138 [34.764846, -118.732931] at Quail Lake. This lake is part of the aqueduct system, and it straddles the San Andreas. That’s probably not such a bad thing – a fault rupture wouldn’t affect the lake, and repairing an offset canal would probably only take a day or two. No worries (?).

Go north on I-5, which follows the San Andreas through Gorman and up to the Grapevine summit. The fault is right under the freeway at the summit -- talk about a divided highway!

Take the exit for Frazier Mountain Park Road. You might want to stop where you can look around at this unusual valley.

Nearby Fort Tejon was the approximate epicenter of California’s biggest historic earthquake, the M7.9 quake in January, 1857. 225 miles of the San Andreas ruptured, and slipped up to 30 feet.

~ END OF TRIP ~

Head back to the Southland by going south on I-5.

Upcoming Trip: Frazier Park to Carizzo Plain National Monument

B.S. – Urban Myths

Urban myths about the San Andreas could be their own blog! Here's the big ones, so to speak:

1. In a giant earthquake, California could fall into the ocean. False! Evidence along the coast shows that California is doing the opposite -- gradually rising out of the ocean! In places like Montana de Oro State Park near Morro Bay (see other trip), you can see as many as 9 old beach levels like stair-steps up the hillsides. Ever notice that along most of the central and northern coast, the beach is down below cliffs? The top of the cliffs are the old beach! The crust has lifted up that much, so that sea level is now down where we're used to it being and the old beaches are left high and dry.

2. The San Andreas could cause a tsunami. False! Because it is a strike-slip fault, meaning the two sides of the fault move horizontally past one another, the San Andreas cannot cause the uplift or down-drop of the seafloor needed to form a tsunami. (The San Andreas is offshore of the Golden Gate, and in places farther north).

3. Scientists can really predict earthquakes, but are covering it up for [insert conspiracy theory here]. False! Boy, no one wants to predict earthquakes more than seismologists! But so far the problem has turned out to be more complex than driving a remote-control car on Mars, creating the world-wide web, removing brain tumors, or making candy bags that are silent and don't explode when you open them.

4. The San Andreas is the most dangerous fault in the world. False! It's not even the most dangerous fault in the U.S.! That's because for most of its length, the San Andreas crosses remote or sparsely populated areas. There certainly are short exceptions to that, but California is well-prepared for earthquakes and most of the population does not live near this fault. In contrast, the Cascadia subduction zone extends under all the cities from southern Oregon to Vancouver, British Columbia and is capable of earthquakes bigger than the San Andreas -- 8's compared to 7's. And the New Madrid fault zone in NE Missouri to southern Illinois has had earthquakes nearly magnitude 8, and the older buildings in cities & towns in that part of the Midwest are not engineered for earthquakes.

M.S. – More Science

Visit http://scedc.caltech.edu/recent/index.html to see recent earthquakes in California and Nevada, and browse their other pages for lots more information.

Ph.D. – Piled Hip-Deep

Good summary: http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/earthq3/

Better in-depth document: http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/pp1515

Urban myths about the San Andreas could be their own blog! Here's the big ones, so to speak:

1. In a giant earthquake, California could fall into the ocean. False! Evidence along the coast shows that California is doing the opposite -- gradually rising out of the ocean! In places like Montana de Oro State Park near Morro Bay (see other trip), you can see as many as 9 old beach levels like stair-steps up the hillsides. Ever notice that along most of the central and northern coast, the beach is down below cliffs? The top of the cliffs are the old beach! The crust has lifted up that much, so that sea level is now down where we're used to it being and the old beaches are left high and dry.

2. The San Andreas could cause a tsunami. False! Because it is a strike-slip fault, meaning the two sides of the fault move horizontally past one another, the San Andreas cannot cause the uplift or down-drop of the seafloor needed to form a tsunami. (The San Andreas is offshore of the Golden Gate, and in places farther north).

3. Scientists can really predict earthquakes, but are covering it up for [insert conspiracy theory here]. False! Boy, no one wants to predict earthquakes more than seismologists! But so far the problem has turned out to be more complex than driving a remote-control car on Mars, creating the world-wide web, removing brain tumors, or making candy bags that are silent and don't explode when you open them.

4. The San Andreas is the most dangerous fault in the world. False! It's not even the most dangerous fault in the U.S.! That's because for most of its length, the San Andreas crosses remote or sparsely populated areas. There certainly are short exceptions to that, but California is well-prepared for earthquakes and most of the population does not live near this fault. In contrast, the Cascadia subduction zone extends under all the cities from southern Oregon to Vancouver, British Columbia and is capable of earthquakes bigger than the San Andreas -- 8's compared to 7's. And the New Madrid fault zone in NE Missouri to southern Illinois has had earthquakes nearly magnitude 8, and the older buildings in cities & towns in that part of the Midwest are not engineered for earthquakes.

M.S. – More Science

Visit http://scedc.caltech.edu/recent/index.html to see recent earthquakes in California and Nevada, and browse their other pages for lots more information.

Ph.D. – Piled Hip-Deep

Good summary: http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/earthq3/

Better in-depth document: http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/pp1515

You can also do a web search like this: san andreas site:usgs.gov

Websites:

Fort Tejon earthquake: http://scedc.caltech.edu/significant/forttejon1857.html

San Fernando earthquake: http://scedc.caltech.edu/significant/sanfernando1971.html

Whittier earthquake: http://scedc.caltech.edu/significant/whittier1987.html

Northridge earthquake: http://scedc.caltech.edu/significant/northridge1994.html

Fort Tejon earthquake: http://scedc.caltech.edu/significant/forttejon1857.html

San Fernando earthquake: http://scedc.caltech.edu/significant/sanfernando1971.html

Whittier earthquake: http://scedc.caltech.edu/significant/whittier1987.html

Northridge earthquake: http://scedc.caltech.edu/significant/northridge1994.html